What is Nafithromycin?

- Nafithromycin (development code WCK 4873) is an orally bioavailable ketolide developed by Wockhardt Limited with broad spectrum antibacterial activity against respiratory pathogens: Gram-positive bacteria such as S. pneumoniae and S. aureus and Gram-negatives such as Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydophila pneumoniae.

- Nafithromycin (brand name Miqnaf®) was approved by India’s CDSCO on January 2, 2025, for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP).

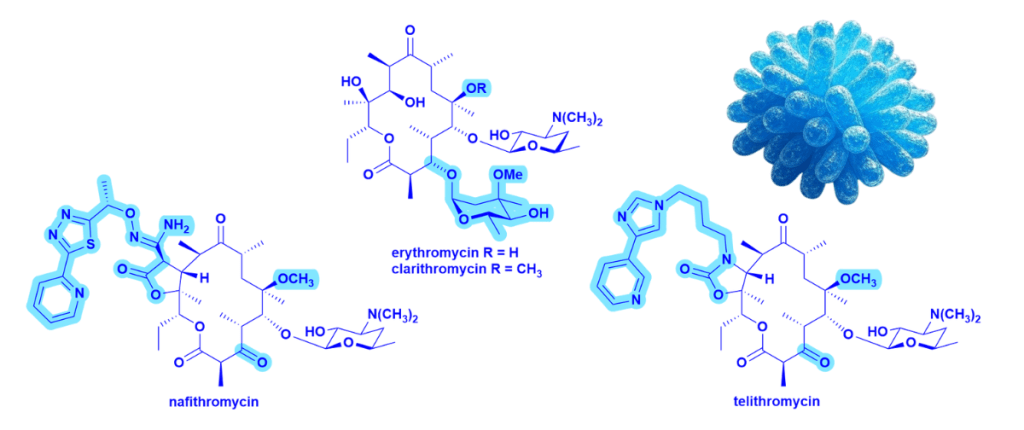

- Nafithromycin is the second ketolide ever approved globally, the first was telithromycin (approved in 2001), which is no longer in use.

Table: Differences between 14-membered macrolides such as erythromycin and clarithromycin and the ketolides nafithromycin and telithromycin – see structures in the figure below.

| Features | Macrolides | Ketolides |

| C3 cladinose | Present | Removed and replaced with a keto group |

| C11–C12 carbamate/aryl-alkyl extension | Not present | Added side chain improves ribosomal binding and helps to overcome some resistance mechanisms |

| Overall binding | Binds to domain V of 23S rRNA | Binds to domain V and domain II of 23S rRNA → stronger binding |

Why It Matters

- Nafithromycin targets drug-resistant CABP, a major killer with over 3 million deaths globally yearly with India bearing ~25% of this burden.

- Nafithromycin is India’s first ‘home grown’ antibiotic to be granted approved.

- For over 25 years, Wockhardt has focused its drug discovery efforts on the discovery and development of new antibiotics to treat MDR infections.

- The company previously introduced levonadifloxacin (IV) and alalevonadifloxacin (oral) in 2019 and continues to build an impressive antibiotic pipeline.

- This is a proud milestone for Indian drug discovery and a timely addition in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. It will be fascinating to watch how the launch unfolds in India, and whether this innovation finds its way to global markets.